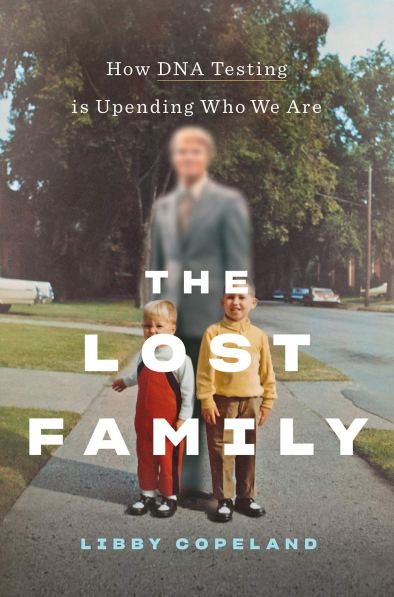

I have been reading a fascinating new book by Libby Copeland. The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are.

I have been reading a fascinating new book by Libby Copeland. The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are.

Ms. Copeland does a wonderful job of summarizing the science of DNA testing in brief and easily understandable ways, while also raising questions about where this new technology is taking us. Family secrets are bursting out of the closets and saying “hello” through Facebook messages.

Consumer DNA testing, such as AncestryDNA and 23andMe, has given rise to the new field called “genetic genealogy.” Yes, this is what allowed me to uncover the roots of my grandfather who came to Missouri from New York City on an orphan train.

The Lost Family struck such a chord in me that I reached out to Ms. Copeland–yes, in a Facebook message. She responded promptly, and we struck up a conversation.

I mentioned that I was a psychologist, and that my dissertation was on how people develop a sense of identity–what makes them who they are, or at least who they believe themselves to be. More specifically, my research was on how family influences an adolescent’s identity development.

Ms. Copeland then asked me a question about how difficult it can be for someone to incorporate new family information after they are well into adulthood. She asked if my profession and education gave me any particular insight into that.

I initially stumbled trying to come up with an answer. I realized I was more comfortable talking about my own experience in researching family history than I was with talking as the “professional, the psychologist.”

I referred her to a couple things I had written, one of them being the talk I gave at the 150th anniversary of the New York Foundling Home, the “orphanage” that sent my grandfather to his new life in Missouri. Ms. Copeland replied that she thought I put it well in that talk when I said: “There is a basic human need to know who you are, and how you connect to this world.”

This got me thinking some more…I developed a talk recently that was to be given at the Missouri River Regional Library in Jefferson City, MO, the town where I grew up, the town where my grandfather had lived his adult life, just a few miles where he had disembarked from that orphan train at age five.

In that talk, I repeat the idea of “our story.” Knowing it, owning it, and being able to tell it. All of this makes us, and our story, real.

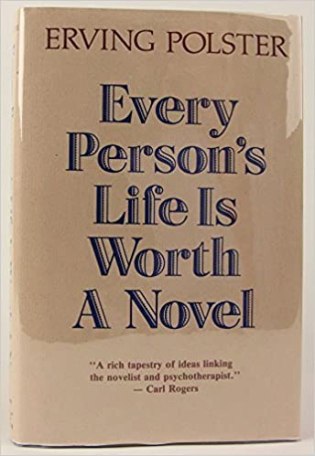

I am a psychologist.  Back when I was in graduate school, my favorite therapy book was titled Every Person’s Life is Worth a Novel. It suggested that a good therapist may think of a client as a character in a great book–what do you need to know about the person to make them more interesting? Keep asking questions until you fill out their personality, their story.

Back when I was in graduate school, my favorite therapy book was titled Every Person’s Life is Worth a Novel. It suggested that a good therapist may think of a client as a character in a great book–what do you need to know about the person to make them more interesting? Keep asking questions until you fill out their personality, their story.

I find myself using that same concept in my genealogy work. I don’t just want to discover my ancestor’s name and date of birth. I want to learn their story as best I can uncover it–what did they do, think, feel? What was it like to be them. How does all that contribute to who I am? Every story I uncover becomes part of my story, part of who I am.

Every person in my family tree has a story to tell. Some seem better-suited to a best-selling book than others. But then I remember the main premise of Every Person’s Life is Worth a Novel…and that is…Everybody is fascinating–it’s just that some people hide it better than others…

So, as a psychologist, amateur historian, and someone always wanting to learn more about myself, there are always more stories to discover. And for me, that is part of how I know who I am, and how I connect to this world.